By: Eric Markowitz | Oct. 16, 2018

A few weeks ago, I stumbled across a rather puzzling interview with Robert Dudley, the CEO of BP, in the pages of the Washington Post.

Midway through the profile—a sort of mea culpa for the disastrous 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster—Dudley says: “If someone said, ‘Here’s $10 billion to invest in renewables,’ we wouldn’t know how to do it… Our shareholders want us to get involved [in renewables], but they also want to make sure we’ll allocate their capital carefully.”

I paused to think that about that. It appears that Dudley’s overarching point is that while BP is committed to making several small investments in new energy technologies, the company is not yet willing to make any substantive adjustments to its business model. “The best thing we can do is get a balance sheet that’s strong,” Dudley said in another interview with Axios earlier this year. “At the right moment, if and when it makes sense , we’ll be in a position to make a big bet.”

“ If and when it makes sense. ” What a remarkable statement. Right now, in the back half of 2018—following a dire report on climate change from the United Nations—it’s becoming increasingly apparent to us that we may be on the cusp of one of the most massive strategic and business reorganizations in human history. Simply put: We believe the multi-trillion-dollar energy market is being disrupted. Entrenched industries that have historically profited from dirty, pollution-causing, greenhouse-emitting fossil fuels will find their business models in chaos. Upstarts and innovators offering efficient solar and wind systems, large-scale grid-level batteries, and electric car makers will drive us into the future.

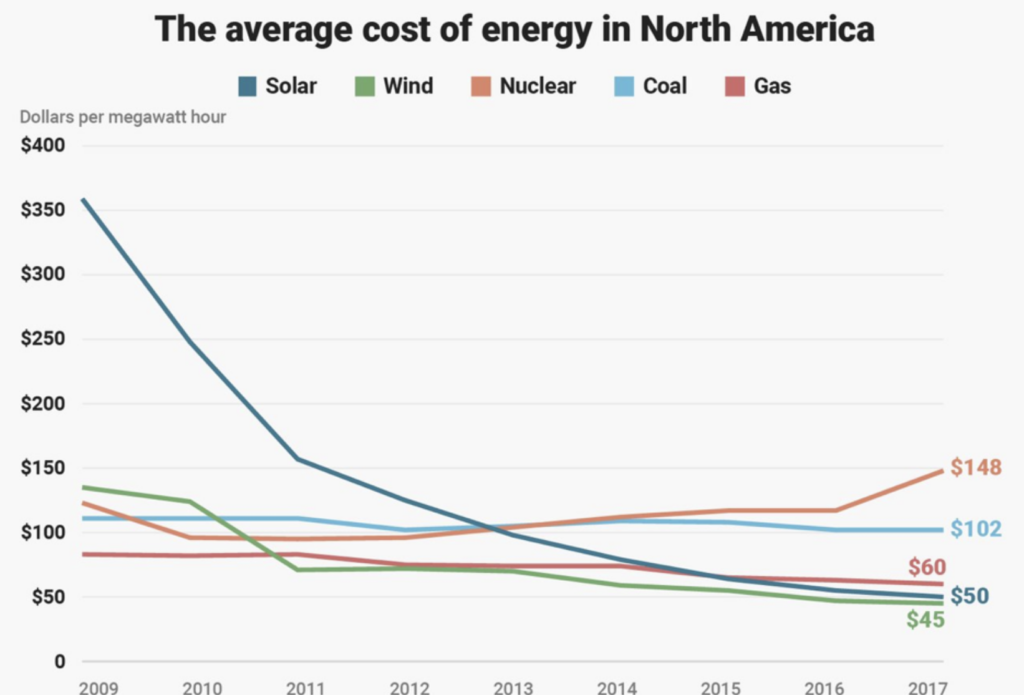

Driving these changes are not altruism or even care for the environment: it’s cost. The cost for solar and wind energy has fallen dramatically in the last several years. A recent report from Lazard , for instance, finds that energy prices from utility-scale solar plants (i.e. plants that produce electricity that feeds into the grid) decreased 86 percent since 2009.

The inflection point is nearing, and it’s not just the cost of the energy that’s dropping, it’s the cost of building the plants that’s dropping as well. According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF), the cost of new solar plants dropped 20 percent in the past 12 months alone. Meanwhile, onshore wind prices dropped 12 percent, according to BNEF. But perhaps even more importantly, the costs for grid-level lithium-ion batteries—which is the key to the puzzle of large-scale energy distribution—have plummeted a whopping 79 percent since 2010 (thanks in large part to the Gigafactories), according to BNEF as well.

So, back to BP and the other oil companies. Where does this lead them? Are they too late? Are they actually investing enough to prepare for this massive change?

To answer this question, I called up Chris Goodall, a clean energy expert and author of the book, The Switch: How Solar, Storage and New Tech Means Cheap Power for All . Goodall is one of the world’s foremost researchers on the massive energy disruption, so I posed the question to him: Are oil companies making the transition quickly enough to renewables?

“The people in the fossil fuel industry are generally so ignorant about the evolution about the technologies that are going to eventually eat away at their foundation,” he told me. “They’re so ignorant that they don’t realize what’s happening until it’s too late.”

He continued, “The bets they’re making are tiny, and the only reason they’re doing them is to be able to say, “Yes, we’re keeping an eye on renewables, and when the time comes, we’ll be making the transition to renewables…. What I can say to you, with absolute and total certainty, is by the time those guys know what they’re doing, it’ll be too late. It’s getting to be too late already.’ Even companies at the forefront of this are behind.”

Goodall’s explanation of the situation is straight out of the Innovator’s Dilemma playbook: At the moment, the cost of oil exploration and drilling has relatively low level risk—technically speaking. On the other hand, any massive capital expenditure on an unproven business model is met internally with skepticism—perhaps even cynicism about renewables. But the fact is, Goodall says, we’re moving in that direction whether Big Oil likes it or not. “The changes which look so small at the moment,” Goodall says, “are indicative of a trend that are going to result in a very steep decline at some point in the future.”

In my mind, the “small bet” approach is exactly the opposite of how CEOs need to be thinking in disrupted industries: What seems “careful” today could actually be quite dangerous if the the paradigm of your business is fundamentally shifting to a new reality. The fact is, prices for solar, wind, and battery storage are dramatically declining. They’re dropping so rapidly, in fact, that that renewable energy sources are edging many forms of fossil fuel power—including natural gas.

It’s not just BP that’s seemingly confused about the future. Earlier this year, Fortune profiled the CEO of Shell. The story took on a similar bent: The massive oil company was aware of the changes it needed to make, but only some time in the distant, hypothetical, we-don’t-exactly-when future. From the piece:

“Fueling this shift are newly affordable alternatives to oil and gas—notably solar power, wind power, and batteries. Adding to it are ever tougher government constraints on greenhouse-gas emissions: Europe, China, and much of the rest of the developing world are moving to curb carbon even as President Trump pulls the U.S. out of the Paris climate accord.

Ben van Beurden, Shell’s CEO, vows that won’t happen. “We won’t be sitting ducks,” the 59-year-old Dutchman tells me in an interview in his corner office at The Hague. “We are going to adapt.”

The problem is that the right path forward for the oil majors is less clear than ever before. In the past, “there was a funnel of outcomes that we had to navigate in, where a conservative approach could still work,” says van Beurden. “What is a challenge at the moment,” he says, “is that we don’t know anymore where the future will go.”

“We don’t know anymore where the future will go.”

Again, I personally doubt van Beurden doesn’t have a directional knowledge of where the future is heading. It’s simply, in my view, that the dynamics of his business model do not currently justify a massive shift away from oil and gas exploration. We have seen this sort of disruption across a variety of industries. For instance, Kodak held the first patents for digital photography in the mid-1970’s. But it was a case study of corporate inertia: they made too much money on printed film to justify any big moves away from their core business into the unknown area of digital photography. The energy industry is facing a similar dynamic.

So despite the PR-friendly campaigns and the relatively modest bets, I happen to believe that Shell and BP might actually be sitting ducks. One analysis by EcoWatch found that, despite all the platitudes about “adapting” and “investing,” the reality is that, in the last five years, Big Oil has invested, cumulatively, just over $3 billion on renewables acquisitions—predominantly on solar. “It is peanuts compared to the tens of billions the companies spend looking for oil,” the author wrote earlier this year.

Time will tell how what will happen to Big Oil, but one thing I’m relatively certain about: We’re on the cusp of massive change, and the future is heading towards renewables. Will it be led by the incumbents? If history teaches us anything—probably not. There will be massive winners in this new market—and equally massive losers. The energy revolution is real, and it’s happening quicker than most people believe. And whether or not Big Oil can adapt is will be of the most exciting business dramas to play out over the next decade.

Nightview Capital, LLC does not accept responsibility or liability arising from the use of this document. No document or warranty, express or implied, is being given or made that the information presented herein is accurate, current or complete, and such information is always subject to change without notice. Shareholders and other potential investors should conduct their own independent investigation of the relevant issues and companies involved in this article. This document may not be copied, reproduced or distributed without prior consent of Nightview Capital. Arne Alsin and Nightview Capital clients are currently long Amazon (AMZN) stock and call options, and stand to benefit if the trading price Amazon increases.

The opinions expressed herein are those of Nightview Capital, LLC and Kingsmill Bond and are subject to change without notice. The company (or companies) identified or referenced herein is an example of a current or potential holding or investment target and is subject to change without notice. This information should not be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security. It should not be assumed that any of the investments or strategies referenced were or will be profitable, or that investment recommendations or decisions we make in the future will be profitable. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Nightview Capital reserves the right to modify its current investment views, strategies, techniques, and market views based on changing market dynamics. This article contains links to 3rd party websites and is used for informational purposes only. This does not constitute as an endorsement of any kind. Nightview Capital, LLC is an independent investment adviser registered in the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, as amended. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. More information about Nightview Capital including our investment strategies, fees, and objectives can be found in our ADV Part 2, which is available upon request. WRC-19-10