By Daniel F. Crowley, CFA

Portfolio Manager, Managing Partner | Nightview Capital

On the Ground in China

I’ve always believed you can’t understand a place by reading reports in an office thousands of miles away. Numbers on a page are useful, but they don’t tell you how a city feels when you walk its streets, what people are talking about over lunch, or how energy buzzes—or doesn’t—in the air.

So I went to China myself.

Two weeks there gave me the beginning of a kind of perspective you just can’t get from a spreadsheet. What follows isn’t a grand theory or an investment manifesto. It’s simply a set of observations gathered on the ground, snapshots that together may help us think more clearly about where China is heading, and how those currents might shape the opportunities—and risks—for investors like us.

What’s clear to me is that China is no longer the “world’s factory.” It is rapidly becoming the world’s innovator—or at least the fast-follower with state-sponsored scale.

For American investors, three themes stand out:

1. EVs Are the Next Great Export

China’s EV makers are not just competing domestically; they are preparing to export. Already, brands like BYD are entering Europe. The combination of lower costs, strong design, and vertically integrated supply chains gives them a formidable advantage. For

U.S. investors, I believe Tesla remains the clearest way to play this trend—but keep an eye on how Chinese brands pressure global pricing.

2. Robotics Could Be China’s “iPhone Moment”

If humanoid robots move from prototype to mass production, China could leapfrog into dominance. The state’s commitment is unmistakable. Yet outside of American Depositary Receipts (ADRs) like JD.com, Xpeng, and a few select others, there are limited ways for U.S. investors to participate directly. Instead, I prefer to look at adjacent beneficiaries: U.S. semiconductor companies, AI software firms, and suppliers of robotic components.

3. Consumer Brands Still Matter

Amid all the industrial ambition, consumer behavior tells another story. In my experience, Starbucks appears to be rebounding and Tesla remains aspirational. Even Macau’s casinos are rebounding. For investors, this suggests that while China is protective of strategic industries, it still welcomes foreign consumer brands—if they deliver quality and prestige.

Now, on to my experience across the country.

Arrival in Shanghai

After years of pandemic-era lockdowns, China’s largest city felt alive. We have become accustomed to news headlines about slowing growth, property bubbles, and capital flight —yet the vibrancy was startling. Streets pulsed with traffic, storefronts teemed with shoppers, and I felt a sense of optimism hanging in the air.

Getting around was easy enough with Didi, China’s equivalent of Uber. We have written in the past that we continue to believe in a bipolar world where many Chinese systems operate in parallel to Western technology platforms. It’s something we have seen since the first internet wave in the early 2000s.

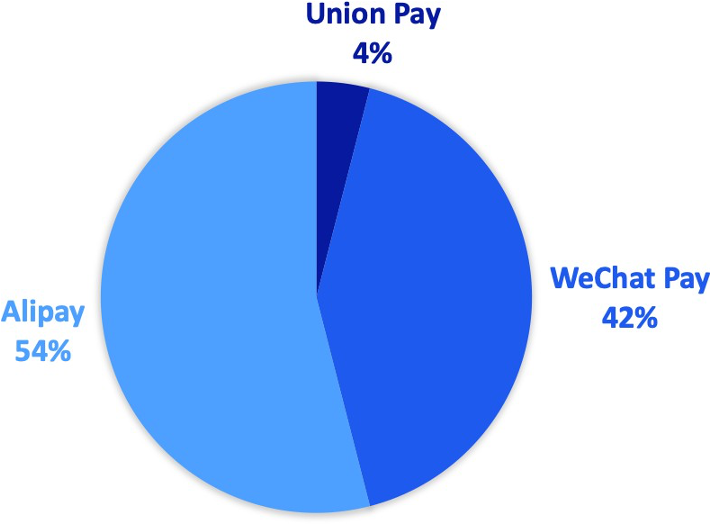

Didi was also embedded inside the country’s broader digital ecosystem. In practice, there are two apps that matter the most in China: Alipay and WeChat. They are not just payment systems but gateways to almost every daily activity—ride-hailing, food delivery, banking, messaging. Together they form a near-total digital monopoly.

Market Share of Mobile Payment Platforms in China

Figure 1: Source CoinLaw, 2025

Alipay itself highlights the difficulty in investing in the undeniable rise and growth in China.

In 2011, Alibaba transferred the Alipay asset out of the company. While it retained only a small ownership stake—and may receive some payout if and when Ant Group eventually goes public—the deal was highly disadvantageous for Alibaba’s foreign shareholders at the time, including Yahoo. (Yahoo and Alibaba Resolve Dispute Over Alipay)

After visiting more than 30 countries, I found China to be one of the more insular places I’ve been—outside of maybe a Myanmar or Cuba, which lack the economic reach that China already wields. That insularity—reinforced by government policy— could slow the spread of its cultural exports abroad.

In many ways it feels like the country is at a crossroads. Betting heavily on moving up the economic value chain globally while still keeping the reins tight on domestic control. This will be difficult as these paths are in many ways in natural opposition.

*America’s cultural soft power remains one of it’s strongest exports.

What is clear is that China’s vast domestic market of 1.4 billion people, combined with its growing regional influence, gives it the potential to sustain an enormous consumer economy. It’s even possible that global markets may matter less than we assume, as the country shifts from an investment-driven model toward one that more closely resembles a Western-style, consumption-led economy.

The EV Revolution: Tesla and Its Shadows

On the streets, one thing was impossible to miss: China has gone electric. Nearly every new car I passed was an EV, humming quietly through the traffic. And everywhere, I could feel Tesla’s shadow—its design cues and interfaces mirrored by the wave of new domestic automakers finding their own momentum.

Every vehicle I saw seemed to carry Tesla’s imprint—panoramic roofs, flush door handles, oversized central screens, even user interfaces that felt nearly identical to Tesla’s dashboard. Having watched how dismissive Western legacy automakers have been of Tesla’s design choices, the contrast struck me even more sharply on the ground.

In a channel check walking through a shopping center in Pudong, I was struck by just how many storefronts were devoted to electric cars. Companies like XPeng, NIO, Li Auto, Zeekr, Denza, VOYAH, GWMAiO, IM Motors were present at many twists and turn of the mall. Inside, the showrooms were striking—each brand’s interior design rivaling, and in some cases surpassing, what I’ve seen from European luxury automakers. NIO’s cabins stood out most: they didn’t feel like cars so much as futuristic living rooms on wheels.

Beyond the sleek aesthetics, what really struck me was the software. Compared to most Japanese and German cars—which often feel a decade behind to me—China’s EV makers have not only matched Tesla’s hardware but are now going head-to-head on the software side. Much of it borrows heavily from Tesla, but the imitations are remarkably polished.

My sense, after seeing it firsthand, is that the most likely outcome is the success of both Tesla and China’s domestic players in a market that’s already twice the size of the United States. That’s bad news for the legacy automakers who once treated China as both their cash cow and their growth engine. For Europe’s luxury brands in particular— long accustomed to unrivaled prestige here—the shift feels especially ominous.

The implications for investors are enormous.

Automobiles are becoming software platforms, and only a handful of companies worldwide seem capable of building that software at scale. Perhaps if Tesla is Apple, then the Chinese EV makers may be Samsung—fast followers with massive domestic

demand and ambitions to export globally (especially in less developed markets). It’s not far-fetched to imagine a future where Chinese EVs play a large part in world markets.

This dynamic marks a sharp break from China’s old role as the workshop for Western brands, churning out other people’s designs. What’s happening now is not just about scale—it’s about profitability. For global investors, it’s a shift worth paying close attention to.

Infrastructure as Strategy

Traveling by bullet train between cities underscored the other side of China’s economic miracle: infrastructure. Trains ran at 220 miles per hour, spotless, punctual, and cheap. Later, departing Beijing’s Daxing International Airport, I was reminded of America’s decaying airports.

The contrast could not be sharper.

In China, infrastructure is strategy. For forty years, growth was built on cheap labor and loose environmental rules; today, the playbook has shifted. The state is betting big on entire supply chains it can dominate end-to-end and nowhere is that clearer than in electric vehicles and batteries. From the cell factories to the charging stations, the ‘new energy vehicle’ ecosystem is increasingly Chinese.

The implication is simple: if EVs win, China wins.

We can argue all day about the strengths and flaws of China’s political model. But the truth is that the country’s long string of state-led growth decisions since the Cultural Revolution has, in many ways, worked. The ‘Kingdom of Bicycles’ has transformed into the world’s largest auto market, and the infrastructure that supports it—trains, subways, electric buses—runs with a speed and ease that often outpaces the United States.

The sense of rising quality of life is impossible to ignore.

Beijing and the Humanoid Bet

The World Robot Conference felt less like an industry expo and more like Comic-Con back home—but here, the celebrities weren’t actors, they were humanoid robots. What struck me wasn’t just the machines themselves, but the genuine excitement on people’s faces. On a Saturday afternoon, entire families had come not for shopping or movies, but to spend the day watching robots.

The Chinese government—through the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and other state organs—seems all-in on robotics. Booth after booth at the conference featured humanoid prototypes, many of them bearing an uncanny resemblance to Tesla’s Optimus. Once again, Tesla appears to have set the template, and China is racing to perfect its own versions.

What was real versus vaporware was harder to judge. But what was undeniable was the enthusiasm and scale. Dozens of companies, thousands of attendees, and full government backing.

(There was also a robotic dog with a fake machine gun strapped to its back being lovingly petted by children—proof that Black Mirror has gone mainstream—but let’s stay focused on the sunnier side of robotics…)

For investors, this matters. Robotics—like EVs—represents a massive total addressable market, and whoever cracks humanoids could end up owning the next industrial revolution. And just as with electric vehicles, the Chinese focus isn’t only on the finished product—it’s on controlling the entire supply chain that feeds it.

For American investors, though, there’s a catch: there aren’t many pure-play Chinese robotics companies listed on public markets, and the private ones are often too opaque and risky to touch. Aside from giants like JD.com—which had one of the flashiest booths at the conference—most of the action is happening behind private walls.

And because building humanoids will be so capital-intensive, it’s hard not to think the real winners may be the integrated tech conglomerates and ambitious EV makers like XPENG, either through their own R&D or through acquisition. China’s massive bet on humanoid robotics only underscores how critical Tesla’s own work on Optimus could become—as a necessary counterweight to Beijing’s ambitions.

Coffee and Culture Wars

One surprising note amid the tech obsession: Starbucks.

In both Shanghai and Beijing, Starbucks stores were buzzing—full, spotless, and aspirational. The brand looked healthier than I expected, especially given the rise of Luckin Coffee, which I only stumbled upon once, tucked inside a rather tired-looking storefront. It’s just one traveler’s impression, of course, but in light of the recent headlines about a potential sale of Starbucks’ China assets (we dug into the company quite a bit last year), it’s clear the company still commands real brand equity here.

Macau: A Bet on China’s Middle Class

From Beijing, I flew to Macau—a short hop, but a world apart. The skyline glows like a neon shrine to casinos, and the city’s fortunes rise and fall with gaming revenue. In 2019, its casinos pulled in six times more gross gaming revenue than Las Vegas. Today, this special administrative region boasts one of the world’s highest GDPs per capita— built almost entirely on gambling, with little in the way of diversification.

COVID-19 nearly broke Macau. For years, the casinos stood half-empty, their neon glow a reminder of an economy built on a single pillar. Now, the recovery is underway. At The Londoner—a sprawling property owned by Las Vegas Sands—the baccarat tables were busy again, the casino floor humming with energy. Still, Macau’s fortunes rise and fall with the Chinese consumer. It was booming when mainland incomes were climbing; if China’s economy regains its momentum, Macau remains a leveraged bet.

These are companies with huge, developed assets and taken as a basket — we believe represent a highly attractive opportunity to own great assets at attractive prices. And

while there is some risk of mainland Chinese gaming moving throughout Asia (Macau was basically a monopoly for years) we believe the overall growth of the Chinese consumer will more than counteract this.

For investors, the angle is clear: U.S.-listed companies like Las Vegas Sands or Wynn Resorts offer exposure to China’s gaming market with American accounting and governance standards. As we have discussed investing in Chinese ADRs poses a degree of risk. We feel ADR allocations are justified on individual bases, but we would always prefer to own U.S. domiciled companies.

Hong Kong: An Identity in Flux

Hong Kong felt different. Once the bridge between China and the West, it now feels in limbo. Locals spoke of stagnant growth post-COVID, and the city seemed caught between its heritage as a global financial hub and its integration into mainland China.

Tesla’s presence was strong, but the broader economy felt subdued compared to Shanghai’s vibrancy. For investors, Hong Kong’s relevance may lie less in its economy and more in its geopolitical role—a testing ground for how China manages integration without full absorption.

The New Energy Conference: Betting the Supply Chain

Back in Shanghai, I attended the New Energy Vehicle Technology and Supply Chain Conference. If the robot conference was about vision, this was about execution.

Hall after hall displayed companies that formed the connective tissue of the EV revolution: battery producers, component suppliers, charging infrastructure firms. The sheer density of activity was stunning.

It reinforced a central truth: China doesn’t just want to sell EVs. It wants to control the entire supply chain—from lithium refining to final assembly. This strategy mirrors its earlier dominance of solar panels, rare earths, and steel. If successful, it positions China as an indispensable hub of 21st-century transportation.

The Risks

Of course, no analysis of China is complete without acknowledging risks. Geopolitical tensions loom large: tariffs, sanctions, and the possibility of decoupling. Government intervention is another wildcard. The same state that fuels robotics growth could also crack down on tech firms overnight. And demographics—with a shrinking population— pose long-term challenges.

Perhaps the deeper risk for investors, though, is this: even if new industries like EVs and robotics succeed, who actually benefits? Do the profits flow to shareholders—or do they get captured by the state, or competed away in a race-to-the-bottom version of capitalism where margins vanish as companies outspend one another? It’s a reminder that in China, growth doesn’t always translate into returns, at least not for outside investors.

That said, we’ve come away convinced that participation in China is no longer optional. Even if it doesn’t mean buying shares of Chinese companies outright, the country’s economic gravity is impossible to ignore. Supply chains, commodity markets, and consumer demand are now so deeply interwoven with China that every investor— whether they realize it or not—already has exposure. The real question isn’t if you’re involved in China, but how you choose to engage, and whether you’re prepared for the risks that come with it.

Conclusion: Balancing Opportunity and Risk

As I boarded my flight home, I felt two things at once: excitement at the pace of innovation, the sheer scale of ambition, the sense of a country sprinting toward the future—and unease about what that means for American competitiveness.

For the past five years, global investors have dramatically under-allocated to China relative to its share of world GDP. In many ways, that caution has been justified. But after seeing the energy on the ground, I no longer believe sitting on the sidelines is a viable long-term strategy.

For investors willing to stomach volatility, China is a paradox: opaque yet obvious, risky yet irresistible. You can tap into its growth indirectly—through Tesla, Starbucks, Las Vegas Sands, or U.S. chipmakers—or directly through Chinese ADRs, with all the political baggage that entails. The story of EVs, robotics, and supply chains is increasingly being influenced by what happens in China. Tread carefully.

Disclosures

The opinions expressed herein are those of Nightview Capital and are subįect to change without notice. The opinions referenced are as of the date of publication, may be modified due to changes in the market or economic conditions, and may not necessarily come to pass. Forward-looking statements cannot be guaranteed.

This is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any particular security. There is no assurance that any securities discussed herein will remain in an account’s portfolio at the time you receive this report or that securities sold have not been repurchased. It should not be assumed that any of the securities transactions, holdings or sectors discussed were or will be profitable, or that the investment recommendations or decisions Nightview Capital makes in the future will be profitable or equal the performance of the securities discussed herein.

Nightview Capital reserves the right to modify its current investment strategies and techniques based on changing market dynamics or client needs. While Nightview uses sources it considers to be reliable, no guarantee is made regarding the accuracy of information or data provided by third-party sources.